Open Review of Management, Banking and Finance

«They say things are happening at the border, but nobody knows which border» (Mark Strand)

THE NEW EUROZONE RISK MORPHOLOGY

by Marcello Minenna

ABSTRACT: Ten years into the global financial crisis, the euro area is struggling to get back on a path of stability and growth. Apart from international factors, there are endogenous reasons that develop along two main risk backbones: large and persistent competitive gaps, which contrast center and periphery, and risk segregation, which hinders effective progress towards a fiscal union. The present paper explores these two risk backbones and measures them through economic and financial indicators that are closely related to each other. The critical values of these indicators highlight a matter of unsustainability of the EMU membership, as hinted by the rising Euro-skeptic debate. This has resulted in a confrontational attitude of most distressed countries with the European institutions, which in turn has translated into higher sovereign risk premia as in the recent Italian experience. The recipe for these problems cannot be limited to a tighter regulation for the public sector and for banks: it must open to risk sharing in order to definitively defuse centrifugal forces, remove financial and commercial imbalances, and pave the way for a fiscal union with a federal budget, a unified debt market and a single finance minister.

SUMMARY: 1. Introduction. – 2. Competitiveness gap risk – 3. Risk Segregation Paradigm. – 4. Unbundling the risks of the Eurozone periphery. – 5. Proposals to amend the Eurozone risk morphology. – 6. References

1. Ten years into the global financial crisis, the Eurozone is struggling to get back on a path of stability and growth. The recovery seen in recent years is crunching in the wake of the slowdown in the international economic cycle [IMF, 2018] especially in relation to the escalating trade tensions, Brexit-related uncertainty, renewed nuclear tensions and the increased volatility of raw materials’ prices.

However, the problems of the Euro bloc are also the result of a progressive stratification in which the original flaws and the architectural incompleteness of the monetary union have added to inadequate anti-crisis policy measures. So far none of the open issues of the Euro area has been properly addressed, starting from the mandate and constraints of the monetary authority. The monetary orthodoxy of a central bank mandate only in terms of price stability and inflation target – and the (related) prohibition of monetary financing of governments’ spending – is made particularly critical by the lack of serious forms of fiscal integration. In this framework the ECB inflation target («below, but close to 2%») is condemned to remain referred to the Eurozone as a whole and, therefore, to be pursued on average across member countries. This is equivalent to saying that the architecture of the Euro area admits inflation differentials between its components despite they share the same currency [OTERO-IGLESIAS, TOKARSKI, 2018].

As long as credit risk has remained essentially unknown to financial markets, inflation heterogeneity has been regarded as the main divisive edge between Eurozone members. But the onset of the crisis has unveiled another stress factor: the possibility of outright sovereign defaults arising from the lack of a lender of last resort and the consequent dissolution of the single interest rate curve that had characterized the early years of the monetary union.

The above arguments allow to identify two main ‘risk backbones’ that have concurrently contributed to build up the current Eurozone risk morphology([1]).

The first – which in this paper is called competitiveness gap risk – concerns the large and undue competitiveness gaps that over time have been accumulated across member countries because of inflation differentials and sovereign yield spreads. The winners/losers’ divide produced by persisting gaps endangers the membership feeling of losers pushing them to look for alternatives. In order to gauge the size of these gaps the paper considers two indicators regarding the financial sector and the manufacturing sector, respectively: real (or inflation-adjusted) sovereign yield spreads and the Financial Real Effective Exchange Rate (F-REER) defined as the effective exchange rate after adjusting both for inflation and for differences in sovereign yields. The relevance of the first indicator is quite intuitive: core activity of banks and other financial players is strongly affected by their funding costs that are closely related to domestic inflation and to the credit worthiness of their national governments. In turn, by affecting lenders’ margin profits, these factors also influence the funding costs of industries resident in the different countries shifting the break-even point of their business especially in a bank-centered environment as the one of the Euro bloc. From this standpoint, the F-REER is an indicator that summarizes the different strength with respect to the terms of trade along with the competitive advantages associated with the opportunity to rely on lower interest rates. Information conveyed by these two indicators reveals huge distances between countries that cannot rely on exchange rate adjustments to rebalance highly asymmetric situations.

The second ‘risk backbone’ is the risk segregation paradigm adopted by private investors resident in core countries and by the Eurozone ruling class since the notorious Deauville meeting in October 2010. Banks and other financial institutions located in the center of the Euro area have imposed a sort of ‘quarantine’ on the public and private sectors of peripheral economies: since 2008, Franco-German lenders have scaled down their peripheral exposures by over two thirds. This was a clear statement of mistrust for market participants who began to speculate against the survival of the Euro further deflating the market value of peripheral debts. Even selective risk sharing interventions agreed from time to time by the Euro-bureaucracy to the benefit of individual countries in the periphery have not been effective exceptions to the risk segregating attitude: rather, they have been twin bailouts that – by avoiding extreme outcomes in the beneficiary country – have allowed French and German banks to suffer losses on their exposures to that country and to gain the time needed to disinvest [MINENNA, 2018a].

Extraordinary ECB measures – such as 1 trillion euros Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs) and the Quantitative Easing (QE) – have contributed to gain time, but for timing, size and constraints have contributed to pathological phenomena: nationalization of the government debt of peripheral States, negative yields, large and unprecedented Target2 imbalances.

Precisely Target2 is the last act of the risk segregation paradigm: as long as the Eurozone survives without losing ‘pieces’, Target2 imbalances matter little; but, in case of exit by a debtor nation, its National Central Bank may be tempted not to settle the debit balances with the rest of the Euro-system, imposing a consequent loss on the NCBs of the other countries. Not surprisingly, the rise of Euro-skeptical forces in recent years in many member countries has preoccupied creditor countries, pushing them to elaborate various proposals to revise the Target2 system in order to get immunized from adverse events.

Also real sovereign spread dynamics help to measure this segregation process since they represent the risk premium required to peripheral countries with respect to the German safe haven. And, it is not a coincidence that, since the eruption of the crisis, this quantity is strictly linked to the evolution of net Target2 balances.

The landscape outlined by the above described ‘risk backbones’ raises serious concerns about the compactness and resilience of the Eurozone. A confirmation comes from the recurrent surge of the redenomination risk in reaction to domestic developments that question the membership of a State, as recently happened in Italy and, before, in France (although to a lesser extent), and Greece. These internal developments are the result of a growing unsustainability of the current Eurozone set-up for several member countries, which manifests itself in various ways (social discontent, impossibility to implement expansive fiscal policies, exacerbation of the Euro-skeptical debate, rise of political forces characterized by a confrontational attitude with European institutions), precisely because of the imbalances and anomalies produced by the competitiveness gaps and systematic risk segregation analyzed in this paper.

The two issues qualify the risk morphology of the euro area and their analysis offers a useful map to orientate the EMU reform process and find adequate solutions.

A first area of intervention should address the ECB mandate and constraints. Less than one year after the end of its massive bond-buying program, the monetary authority has resumed buying securities – at a rate of 20 billion euros a month and without setting time limits for the duration of this new program – in order to spur Eurozone inflation and support the economy in front of rising downside risks. Yet, even this second QE edition could have little success [MODY, 2019], as the functioning rules have not changed with respect to the previous edition and, consequently, also the new program could result barely effective in addressing the sources of riskiness and fragmentation of the euro area.

An important move in the right direction would have been to get rid of the capital key criterion in favor of a criterion that is more aligned with the actual needs of each State [MINENNA, 2019a]. A similar change could have been implemented by directing the liquidity injected through assets’ purchases only to highly indebted countries. The ECB has already enacted a similar measure with the Securities Markets Programme (SMP), even if with a limited success because of the modest size and some technical details of the program. The success of a new large-scale round of peripheral bonds’ purchases would depend on how much risk sharing it embeds. To this aim, a similar program should be carefully calibrated with regard to the policy on coupon rebates, the residual life of purchased securities and the identity of the bond buyer (either the NCBs or the ECB). For example, a set-up where earned coupons are remitted to the sovereign issuer and where NCBs purchase only ultra-long peripheral bonds as part of a coordinated intervention with national Treasuries would deliver a certain drop in sovereign yield spreads across member countries. Nevertheless, such a measure would hardly achieve a marked improvement of the Target2 imbalances due to the persisting risk segregation associated with direct NCBs’ purchases.

A more ambitious program would necessarily require a centralization of the purchasing policy at the ECB (implying a full risk sharing on bonds held by the Euro-system) and a larger size of the intervention. Such a move would certainly have a greater impact in terms of normalization of Target2 balances as well as of the shape and slope of the sovereign yield curves, favoring the return on a convergent path.

It remains understood that a complete zeroing of sovereign spreads could hardly ignore a review of the institutional objectives of the ECB with a direct targeting in terms of interest rates as the Bank of Japan has decided in 2016 (so-called yield-curve-control)([2]). In the multi-national environment of the euro area, such a target would operatively require country-specific interventions also to take into account the different inflation dynamics of the involved economies.

A similar revision of the ECB target would have a breaking effect on investors’ expectations and interest rate dynamics, as happened in 2012 in reaction to the announcement of the anti-spread shield (the OMTs).

It goes without saying that the ECB cannot be charged alone with the whole responsibility of making the Eurozone sustainable again. As it was in the intentions of the founding fathers, the monetary union must be completed by a fiscal union, an ambitious goal but attainable provided that the right choices are made and they are implemented gradually.

In this regard, a practical and effective solution would be a step-by-step reform of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) with the aim of realizing – in a reasonable timeframe – a complete mutualisation of Eurozone sovereign risks compliant with market rules and with conduct rules designed to minimize moral hazard.

As explained in a recent work [DOSI, MINENNA, ROVENTINI, VIOLI, 2018], this risk mutualisation would take the form of a supranational ESM guarantee with the ECB financial backing and would include, inter alia, the introduction of a non-redenomination clause on government bonds that benefit from the guarantee. At the end of a transitional period in which sovereign yields of the member countries would be boosted to converge on a common trajectory, the Eurozone would finally be ready to become a fiscal union with a genuine federal budget and a federal debt managed by a single finance minister.

Hopefully the above sketched solutions would gradually deflate the overall risks, bring to physiological levels the above identified indicators of the Eurozone risk morphology (i.e. real yield spreads, F-REER and Target2 imbalances) and ensure long-term stability to the euro area.

2. According to euro advocates, one of the strengths of the single currency would have been the elimination of the exchange rate risk between member countries and (with it) of unfair competition from economies whose growth model was based on competitive devaluations [TILFORD, 2014] to pump exports to the detriment of their neighbors.

Facts have shown, however, that the Eurozone architecture – especially in the interpretation given by the European ruling class – is an equally fertile ground for the development of undue divergences in competitiveness between member countries than the former regime of flexible exchange rates.

The main cause is the inappropriate choice of a partial integration, evidenced by the adoption of the same currency without fiscal and labor market integration and with a common monetary policy that – having to mediate between so different realities – is subject to unavoidable operational limits, especially when considering inflation rates at the level of individual member States.

Compared to the pre-Euro phase, there has been a deterioration in the competitiveness of the Southern European countries (Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Greece) and a simultaneous increase in the competitiveness of the Central-Northern European countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Austria, Luxembourg, France and Belgium) [ENGLER et. al., 2014]. In particular, the entry into the single currency has led to a huge commercial advantage for Germany, which has benefited from a substantial devaluation of its currency compared to the era of the Deutsche mark. The combination of this factor with a policy of wage restraint and low inflation has allowed the German manufacturing industry to subtract important market shares from its European competitors and to consolidate a leadership position in the arena of global trade.

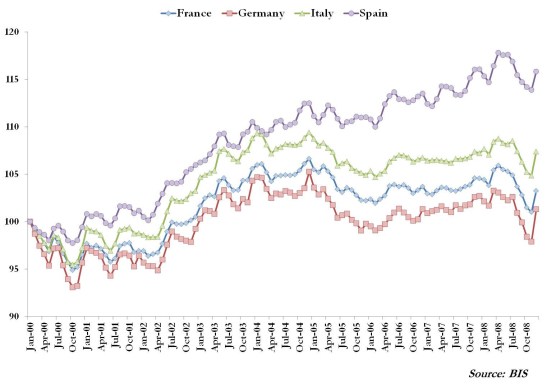

A good representation of this phenomenon is offered – limited to the pre-crisis period – by BIS data on Real Effective Exchange Rates (REER).

Figure 1 illustrates the REER dynamics for selected Eurozone countries over the period 2000-2008. Apart from a somehow correlated pattern (especially up to 2004), most countries have experienced a deterioration in competitiveness, whereas Germany and its allied countries (Austria, Finland and the Netherlands) have enjoyed a devaluation of their REER along a path already undertaken in the immediately preceding years.

Figure 1 – Real Effective Exchange Rate for selected Eurozone countries: 2000-2008 (January 2000=100)

In turn, larger competitiveness gaps have led to within-union external imbalances, as it results from the divergent dynamics of the current account balance of Southern and Central-Northern European countries.

Figure 2 compares the current account balance (as percentage of GDP) of the two subsets of countries from 2000 to 2017, highlighting the prevalence of the described dynamics up to 2008. Then, some form of convergence has shown up, characterized by a recovery in the current account of peripheral countries that, however, is mainly associated with the collapse of imports in the broader context of the collapse of domestic demand caused by the crisis and the austerity policies required by the Euro-bureaucracy.

Figure 2 – Current Account Balance (in % of GDP) of Central-Northern and Southern European countries: 2000-2017([3])

Moreover, the contribution of the current-account surplus to the GDP of Central-Northern countries remains still significantly higher than the one seen in Southern countries: 4.7% against 2.6%.

Among Central-Northern countries, Germany deserves a special mention: since end-2000, its current account balance has posted an unprecedented growth that, after a temporary stop in 2009, has resumed to new record highs with values steadily over 7% of the GDP since September 2014. The maximum was reached in mid-2016 when – pushed by the euro devaluation with respect to the US dollar entailed by the ECB Quantitative Easing – it has arrived to 8.76% in GDP terms.

Entry into the euro area allowed German economy to successfully pursue its mercantilist vocation, supported also by the domestic financial system. In fact, in the pre-crisis period, banks and other professional investors resident in Germany have generously granted credit to neighboring countries in order to finance the external demand for ‘made-in-Germany’ according to a classic vendor financing scheme [MINENNA, 2016].

The subsequent eruption of the crisis has pushed German lenders to close the credit taps to the Eurozone periphery, while it has reserved however other important advantages to the German manufacturing on the financial field, which will be discussed shortly.

Despite the anomaly of the German current account data, the European officialdom has avoided decisive action in this regard [THE ECONOMIST, 2018]. Formally, the European Commission recognizes that excessive and persistent current account surpluses cause an erosion of competitiveness. Since Autumn 2011 it also has set forth specific limits in this regard by including a 3-year backward moving average of the current account balance as percent of GDP over the +6% threshold in the list of macroeconomic imbalances that threaten the well-functioning of the monetary union as a whole([4]). Yet, so far, Germany has received only pale addresses from the Commission, usually in the form of policy recommendations to stimulate domestic demand and imports. For its part, Germany has essentially been turning a deaf ear and its current account is expected to remain the world’s largest in 2018 at a value of about $300 billion [CESIFO, 2018], a position that the country has been holding for many years, placing itself in front of large export-driven economies such as China and Japan.

Inflation differentials affect the relative competitiveness of countries also in relation to the funding costs effectively faced by the government, corporates and households and measured by real interest rates. Paraphrasing Boschen [1994], the real interest rate is the price at which current consumption/investment opportunities via savings can be converted into future consumption/investment.

Also from this point of view the euro is a strange animal compared to the other main currency areas. The major central banks around the world have an inflation target which is combined – more or less explicitly – with some kind of commitment on the real economy. In the case of the FED, for example, this combination takes the form of a dual mandate([5]) with a target both in terms of inflation and in terms of maximum employment. And even where the central bank’s mandate is stated exclusively in terms of price stability, still generally experts talk about ‘flexible inflation targeting’ precisely because the monetary authority also pursues employment and output stabilization together with the inflation target([6]).

In addition, even where they are formally independent from the respective Treasury Ministries, central banks can make open market operations to buy government bonds on the secondary market and, thus, finance government spending through more or less direct actions that obviously impact on inflation.

By virtue of this wide-spread set-up, monetary policy significantly affects the inflation rate and, through this, the riskiness of government debt. In other words, inflation represents an endogenous source of risk for government bonds and, therefore, it is appropriate to examine their yields in nominal terms, i.e. including the inflation risk premium.

At the same time, in most currency areas, inflation is also the main source of risk for public debt securities, whose value for bondholders, in fact, suffers a deduction when money loses its purchasing power.

Inflation risk (together with the exchange rate risk) compensates for the substantial absence of outright default risk because the (more or less explicit) backing of the central bank that acts as a lender of last resort guarantees that the government repays its debt at maturity.

The euro area, however, obeys a different scheme. The ECB primarily pursues a price stability objective with an inflation target «below, but close to 2%». Subject to this objective, it can support the general economic policies of the European Union including those aimed at pursuing full employment and a balanced GDP growth.

More noticeably, the inflation target pursued by the ECB does not have a one-to-one correspondence with any national government, as it refers to the Eurozone as a whole and, thus, it is a weighted average value([7]) between the different member countries. In addition, the ECB is statutorily forbidden to monetize the public spending of any member government.

A prominent consequence of this peculiar set-up – which the same founding fathers of the European monetary union considered transitory pending the upgrade to a full fiscal and political union – is that, paradoxically, the effective ECB ability to affect the inflationary dynamics of individual countries is minimal([8]).

In practice these dynamics end up responding mainly to other impulses (e.g. labor cost, energy prices), which in turn are often driven by idiosyncratic factors at the national level. This makes the euro area naturally predisposed to inflation differentials across member countries.

Looking at the riskiness of public debts, inflation can be regarded as an exogenous source of risk for bonds issued by individual governments within the Eurozone. On the other hand, these bonds – not being guaranteed by the European Central Bank – are endogenously exposed to the insolvency risk of the respective national Treasury([9])([10]).

For these reasons, the comparison between the sovereign yields of the member countries in real terms (i.e. after adjusting for inflation differentials) offers a more correct assessment of their different insolvency risk.

Looking at real sovereign yields over the pre-crisis period – when the odds of a sovereign default were essentially zero – it can be observed that, in a certain sense, even then the Eurozone was strongly fragmented (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Long-term real interest rates for selected Eurozone countries: January 2002 – December 2008

On the one hand, the moderate price growth in Germany has supported relatively high real yields and a reduction in the propensity to invest (without much critical consequences, given the export-driven orientation of the Teutonic economy). On the other hand, several peripheral economies (such as Spain, Ireland, Greece and Italy) have been over-heated by the low real interest rates resulting from a high inflation environment. Spain, for instance, has even experienced negative real interest rates that have contributed to boost the investment boom and the real estate bubble [ODENDAHL, 2014].

Precisely as predicted in 1986 by Alan Walters, the British economist who had advised Margaret Thatcher not to join the Exchange Rate Mechanism (the preparatory phase for the launch of the single European currency), highlighting the inherent instability of a fixed exchange rate system. In the absence of rebalancing mechanisms replacing bilateral exchange rate adjustments, such a system is vulnerable to large gaps between participating countries and to dynamics that amplify economic cycles at the national level.

The advent of the crisis has favored the progressive reversal of these trends, as it emerges at a glance from Figure 4 which shows the trend of 10-year real interest rates of selected Eurozone governments over the last decade.

Figure 4 – Long-term real interest rates for selected Eurozone countries: January 2009 – August 2019

Germany has got increasingly descending real interest rates, which – after having been hovering around the zero threshold for a while – are now steadily negative; similar pattern for France. Italy, Spain and other peripheral countries, instead, have seen rising sovereign yields in real terms as result of two driving forces: a widening credit risk premium – which has boosted their yield curve in nominal terms – and the shift to a deflationary environment.

In recent years, however, there has been a progressive decoupling between the two major peripheral economies – Italy and Spain – mainly due to the different impact of the European rules and supervision and to the different attitude shown by the political leaderships of the two countries towards the Europe (more confrontational the Italian one and more conciliatory the Spanish one). In particular, for Italy the markets have priced a growing sovereign risk because of the climate of political and fiscal uncertainty, also due to the fear of losses from redenomination of the public debt in a new national currency. The perception of these risk factors began to decline only in the summer of 2019 in the face of the reassurances coming from the country’s changed political environment (as well as from the renewed ECB’s accommodative stance).

It is well-established that the crisis has brought to the attention of the financial markets the importance of credit risk not only for the private sector but also for the public sector, starting with the first Greek debt crisis of Spring 2010. Shortly thereafter, Germany and France have agreed that the best way to reduce the risk of contagion was to confine risks in the periphery, avoiding solutions based on risk sharing.

The consequences of this policy have been the dissolution of the single Eurozone interest rate curve, the appearance of sovereign yield spreads and the flight-to-quality, i.e. the flight of investors from peripheral countries towards the German Bund, which has become the safe asset of the entire Euro bloc. At the same time, the crisis of confidence has gradually destroyed the inter-bank market of the periphery through a number of well-known phenomena including collateral discrimination and spread-based intermediation, forcing the ECB to intervene as liquidity supplier of monetary and financial institutions located in the Southern euro area [MINENNA, 2016].

Through the inter-bank market the large and persisting divergence in sovereigns’ funding costs has propagated to the banking sector: given the broad financialisation of modern economies and the high reliance of European businesses and households on banking funding, problems have promptly reversed also on the real economy leading to a prolonged credit crunch with profound recessionary implications. In turn, as in a classical vicious circle, the collapse in economic growth has translated into higher debt-to-GDP ratios making it harder and harder for peripheral governments to remain compliant with a budgetary discipline that – in accordance with the continental predicament for fiscal virtue – was being made even more binding (with amendments to the Stability and Growth Pact and with the Fiscal Compact) despite the foreseeable pro-cyclical effects.

All these phenomena have impacted the competitiveness of the various members of the euro area, making the real effective exchange rate an incomplete indicator of their different competitive strength (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Real Effective Exchange Rate for selected Eurozone countries: 2000-July 2019 (January 2000=100)

In order to take into account the joint effect of the above described disaggregating factors (inflation differentials and sovereign yield spreads) on the relative competitiveness of the real economies of Eurozone members, it is useful to adjust the real effective exchange rate for the part of the sovereign yield of any given country exceeding a threshold that is common to all countries within the monetary union (for instance, the weighted average of the sovereign yields of all member governments). The indicator obtained in this way can be baptized Financial Real Effective Exchange Rate (in brief, F-REER).

Figure 6 reports the evolution of the Financial Real Effective Exchange Rate for selected Eurozone countries, highlighting the progressive consolidation of much larger competitive gaps than those displayed by the standard REER indicator. In mid-2019 the gap between Spain and Germany is 36% in favor of the second, that between Italy and Germany of around 30% (again in favor of Germany).

Figure 6 – Financial REER for selected Eurozone countries: 2000-July 2019 (January 2000=100)

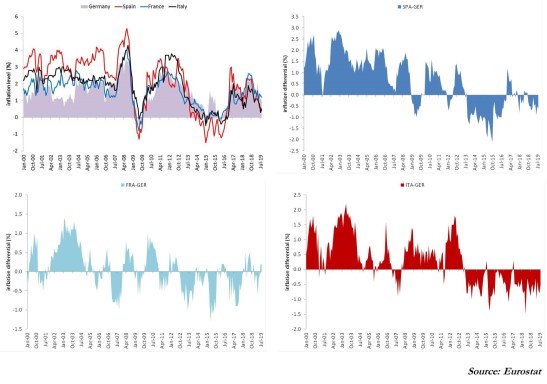

Until the eruption of the crisis, inflation differentials have been the main cause of the growing competitive gaps between member countries. In the following period, however, the contribution of the sovereign spreads became predominant, in line with the market assessment of the credit risk but also – starting from mid-2013 – because of the deflationary impact that the crisis and the fiscal containment policies have had on the peripheral economies. Consequently, inflation differentials between Central-Northern and Southern European countries have progressively shrunk and, then, even changed sign. As shown by Figure 7, this is particularly evident when considering inflation differentials with respect to Germany.

Figure 7 – Inflation levels for selected Eurozone countries and inflation differentials w.r.t. Germany: 2000-August 2019

In the new set-up that took shape since 2014 Germany exhibits among the highest inflation values in the Eurozone, also due to the abandonment of the wage containment policy. Meanwhile, the Bund has retained its status of safe haven and, therefore, yields on German sovereign bonds have remained very low (when not negative) also thanks to the effect of the Euro-system’s purchases under the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), where the capital key criterion guarantees to Germany the highest share of the ECB’s monetary stimulus [MINENNA, 2019a].

The combination of low nominal interest rates and steady but controlled inflation ensures Germany the opportunity to borrow at highly negative real interest rates. Conversely, countries in the periphery of the euro area have begun to face higher interest rates in real terms, which have contributed to hinder government spending and economic recovery.

This is the new face of competitiveness gaps in the post-crisis era and suggests that the real sovereign yield spread is a very good indicator to measure these gaps.

A similar measurement is of particular interest for Italy with respect to Germany([11]). The latter is considered the safest issuer of the euro area, whereas the former is often referred to as the sick of Europe, because of the huge public debt-to-GDP ratio. Nevertheless, Italy is also the only peripheral country which has never received customized financial assistance packages from the European Official Sector; rather it has joined as third contributor after Germany and France to all aid packages granted to the rest of the periphery. And, precisely because of the huge public debt, Italy has also been required to make domestic reforms (encompassing the job market, the retirement expenditure, the budget for public investments, etc.) which have heavily hit its economic and social landscape.

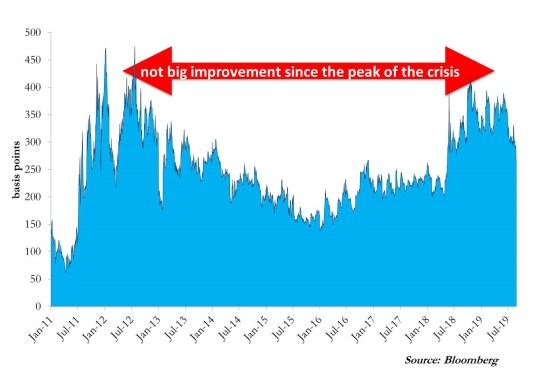

Figure 8 reports the real yield spread between 10-year Italian BTP and 10 year German Bund from January 2011 to August 2019.

Figure 8 – Yield spread between 10-year BTP and 10-year Bund adjusted for the inflation differential between Italy and Germany: 2011-August 2019

Impressively, it can be observed that recent levels of the real BTP-Bund spread are very close to those experienced at the peak of the crisis (late 2011-early 2012). At that time, this indicator had an average value of 350 basis points, more or less the same as the one recorded, on average, over the last 15 months of the observation period.

Apart from a bit of volatility, Italy’s real sovereign spread has not significantly improved over the last seven years: it never went below the 150 basis points floor since mid-2011 and has been almost always above the 200 basis points threshold since September 2016. To be relevant over time, as better explained in Section 4, has been the contribution of the key-factors to the sovereign risk.

Information conveyed by this indicator returns a snapshot of Italy’s risk profile which is less oscillating than the one provided by the corresponding nominal indicator (see Figure 9), revealing that – despite the crisis management toolkit deployed at the European level – Italy’s risk profile has remained critical with little improvement since the peak of the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 9 – Nominal yield spread between 10-year BTP and 10-year Bund: 2011-August 2019

Nor the situation is significantly better elsewhere, even if elsewhere the yield spread with respect to the German benchmark is much more contained than in Italy. This is due to the fact that until recently the spread on Italian government bonds has been incorporating a significant component due to the ‘sovereignism risk’ (and related fear of losses from debt redenomination in a new lira) which instead has been absent for some time in the other peripheral countries of the Eurozone.

In this regard, it is useful once again a comparison with Spain, a country that in recent years has gradually reduced the excess-risk perceived by the markets compared to the core countries, also following its conciliatory attitude towards Europe. It remains understood that even in Spain the spread compared to the Bund in nominal terms shows greater inertia than the one in real terms, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 – Real and Nominal yield spread between 10-year Bonos and 10-year Bund: 2011-August 2019

The relevance of the sovereignism/redenomination risk for the assessment of the markets appears, however, only partially proportionate to the total debt level of a country. In fact, in terms of total leverage – meant as the ratio between aggregate debt (public and private) and GDP – Italy and Spain have been at very similar levels for several years.

Moreover, even in several core countries (e.g. France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) the total debt (public plus private) significantly exceeds the Italian one in GDP terms (see Figure 11).

Figure 11 – Total debt (public and private) to GDP for selected Eurozone countries: 2017

Actually, as soon as one widens the eye to other key indicators, such as the NCBs’ imbalances on the Target2 system, it is straightforward to see how no country (not even Germany) is immune. Still, we are all in the same boat.

The ECB Quantitative Easing has temporarily reduced the distances between member countries; but inflation, growth and unemployment still display relevant differences across national economies, and the lack of a fiscal, political and (authentic) economic union remains the main fragility of the Eurozone. In turn, persisting divergence in economic fundamentals becomes more and more a disaggregating factor that needs to be addressed by the ongoing reform process of the euro area not disregarding the resort to out-of-the blue solutions.

3. The second ‘backbone’ of the Eurozone risk morphology is the risk segregation paradigm adopted by the private sector and by the EU institutions since the eruption of the crisis.

Private investors resident in core countries – Germany, France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – have moved first in this direction. After having contributed to spread the crisis within the borders of the euro area because of their large exposures to US-made structured finance products, banks located in the center of the Eurozone have suddenly cut their credit supply to indebted peripheral economies making them hard to sustain their current account deficits (see previous section).

Then it was the time of the official institutions. At the Deauville meeting of October 2010, the leaders of the first two Eurozone economies confirmed the strengthening of the budgetary surveillance on national governments and the principle of Private Sector Involvement, which subordinates any European financial assistance to the participation of private creditors to losses. The losses on the debt issued by bankrupted banks and corporates as well as those on government bonds in case of sovereign default. The latter despite the prudential regulation continued to consider risk-free all government bonds held by banks, insurance and asset management companies.

The official argument for risk segregation is that each country must be virtuous and rely only on itself, leaving no wiggle room to supranational fiscal transfers or concrete stabilizing facilities in favor of a member hit by asymmetric shocks. It is the well-known argument against a transfer union, which appears more or less explicitly in the positions expressed by economists coming in prevalence from the core countries. This is the case of the manifesto signed by 154 German economists and published by the FAZ in May 2018([12]); but even more moderate and reformist economists are still hesitant to accept concrete steps towards a fiscal policy framework that includes a federal budget and automatic transfers to member countries [BAGLIONI et. al, 2018]

The true version of the story has to be researched in the unwillingness of core countries to undertake authentic risk sharing solutions. In order to preserve themselves from the turmoil in the periphery, these countries have used their influential position within the key Eurozone institutions to strengthen the fiscal discipline in the currency area, pretend harsh internal reforms from Southern countries and let their banks getting rid of the large exposures towards the periphery that had been accumulated in the run-up of the crisis.

A look at BIS statistics on Franco-German banks claims against peripheral economies (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland) provides for clear-cut evidence of these dynamics: from 2008 to 2017 these banks have scaled down their exposures by almost two-thirds (see Figure 12).

Figure 12 – Consolidated exposure of Franco-German banks to counterparties resident in the Eurozone periphery([13])

It is commonly agreed [ALCIDI, GROS, 2013] that the flight of private investors was offset by public capital inflows to the benefit of peripheral countries in the form of official loans and unconventional ECB interventions. This set of measures is usually referred to as risk sharing at the level of the European public sector (apart from the IMF involvement) [MILANO, 2017].

A less emphasized point is that, by means of these risk sharing episodes, the Eurozone leadership has favored the deleveraging of peripheral exposures by lenders from the core countries. German banks, in particular, had intermediated the excess saving arising from the large current account surplus by redirecting those funds to countries such as Ireland and Spain where they were used to boost real estate and investment bubbles [SCHELKLE, 2017].

When the crisis arrived, governments in Germany and France had to face a hard choice to save their banks from the danger of huge losses on their claims towards the periphery: either resorting to funds from their public budgets (at the expense of their taxpayers) or agreeing on financial assistance programs to be granted at the European level to the individual peripheral country that, time-by-time, had arrived close to sovereign default or banks’ collapse [THOMPSON, 2013].

Obviously, they selected option n. 2 by which risky exposures to the periphery were transferred to the whole public sector of the monetary union, and, thus, to all Eurozone governments, including those whose private financial sector had negligible exposures to the beneficiary country up to then.

This ‘twin bailout’ policy began with the first Greek bailout in 2010 [FUHRMANS, MOFFETT, 2010]. In February of that year the consolidated exposure of French and German credit institutions to Greece was of 120 billion dollars, over ten times that of their Italian and Spanish colleagues (see Figure 13).

Figure 13 – Consolidated exposure of German, French and Italian banks to counterparties resident in Greece

In May 2010 the Euro-group gave the green light to 80 billion euros([14]) of financial aid to the Hellenic Republic, which took the form of bilateral loans by Eurozone governments (Greek Loan Facility): this way, the Greek risk was redistributed also on countries that were essentially unexposed such as Italy and Spain. The disbursement for the French government (€11.38 billion) has been just slightly higher than that of the Italian government (€10 billion). And, thanks to this bail out by the official sector, French and – more smoothly – German financial institutions had the time to get rid of their ‘toxic’ Greek claims: as shown in Figure 14, by March 2012 they had almost completely dismantled their sovereign Greek exposures.

Figure 14 – Consolidated exposure of Franco-German banks to counterparties resident in Greece: December 2010-December 2012

After Greece, it came the Irish rescue. The Celtic country had stopped its impressive performance in 2008 following the burst of a massive property bubble inflated by reckless credit. When the collapse in property prices turned most of this easy credit into bad loans, the Irish government had to intervene. Nevertheless, in September 2010 Irish banks were on the brink of the bankruptcy with 26 billion euros (one-fifth of the country’s national income) coming due [BOONE, JOHNSON, 2010]. German and French credit institutions had an aggregate exposure of over 200 billion dollars, whereas claims of Spanish and Italian banks to Irish counterparties amounted to less than 30 billion dollars (see Figure 15).

Figure 15 – Consolidated exposure of German, French, Italian and Spanish banks to counterparties resident in Ireland

Instead of letting private creditors bear some of the losses associated with their unwary lending policies, the Official Sector granted Ireland an 85 billion euro aid package: of these, 45 billion were disbursed by the two bailout funds EFSF([15]) and EFSM([16]) under the financial backing of the European countries. In this way banks of the core countries were safeguarded and risks were transferred to the taxpayers of all member countries. This time it was Germany to reduce its private exposure more with a deleveraging of 58.7 billion dollars between the end of 2010 and the end of 2011, while the indirect involvement of the German government (through the two bailout funds) amounted to less than 15 billion euros.

In mid-2011, it was the turn of Portugal that – to overcome a sovereign debt crisis, a large part in the hands of foreign investors – applied for and received a 78 billion euro financial rescue package, two-thirds of which came again from European governments through funding from the two bailout funds, EFSF and EFSM. At the time, French and German lenders had a total exposure to the Lusitanian country of about 70 billion dollars, second only to that of Spain (first European partner of Portugal); while elsewhere (e.g. Italy), the exposure of the financial system to Portuguese counterparties was laughable (see Figure 16). Aid from the Official Sector allowed Portugal to emerge from the crisis and Franco-German banks had the time to halve their exposure abundantly.

Figure 16 – Consolidated exposure of German, French, Italian and Spanish banks to counterparties resident in Portugal

Same story with the rescue of the Spanish banking sector in 2012. A bankruptcy of Spanish lenders would have caused large impairments to their Germany and French peers, exposed for 140 and 128 billion dollars, respectively (see Figure 17). Not surprisingly Moody’s had cut the rating outlook of six German institutions from stable to negative [GORE, ROY, 2012]. In such scenario the Euro-bureaucracy gave the green light to the transfer of the assets of distressed Spanish banks to a government-owned bad bank (SAREB) whose intervention capability, in turn, was guaranteed by the support of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), established in those months with the contribution of all countries of the euro area. In December 2012, the ESM provided 41 billion euros for the indirect recapitalization of Spanish banks: funds that, in part, served to repay to the German counterparties the loans generously granted before the crisis. Meanwhile countries with a marginal exposure to the Spanish financial sector were called to play their part: 14.4 billion euros the bill for Italy.

Figure 17 – Consolidated exposure of German, French and Italian banks to counterparties resident in Spain

Apart from these episodes, the risk segregation paradigm has recurrently inspired the measures adopted by the Euro-bureaucracy after the emergency years of the crisis. The most striking example has been the second Greek bailout: in March 2012 the Private Sector Involvement has been designed to cut by 74% the Greek public debt not held by the EU and the IMF.

Looking at the whole Eurozone the list of measures that – calling for risk reduction – took care of confining risks within the periphery is long. With regard to the financial sector, it includes the shift to a regulatory framework aimed at legalizing the PSI principle. In August 2013 – after that banks of core countries had been secured also through more or less direct interventions of their respective governments([17]) – it has entered into force the Communication of the EU Commission on the banking sector([18]) that has introduced burden sharing provisions to address banking crises. In essence, in case of bank collapse, any involvement of public funds is conditioned upon a prior reduction in the value of receivables held by shareholders and holders of subordinated debt.

Starting from 2016, the discipline governing this matter has become even more rigid: the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive([19]) has established the bail in, which extends the plethora of private investors called to bear the losses from bankruptcy prior any public sector involvement also to holders of senior bonds and large deposits. In both cases, a main side effect has been the request of a larger risk premium by private investors to fund banks, especially if located in the periphery. At the same time stress tests and asset quality reviews conducted by the European banking supervision have exerted an enduring pressing for fast disposals of non-performing assets, forcing many credit institutions of the Eurozone periphery to fire sale troubled assets to vulture funds and suffer large impairments. Last but not least, there has been the systematic postponement of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), despite it had to be the third pillar of the Banking Union. In such an adverse context it becomes understandable that banks located in the peripheral countries have long maintained the credit to the real economy at subdued level by acting on both the cost and the availability of funds.

Risk segregation has been applied also to the public sector, by means of an extended list of provisions and practices that, ultimately, have spoiled the uniqueness of the yield curve for Eurozone members and fueled the nationalization of the public debts of peripheral governments with critical implications also for the balance sheets of both private banks and National Central Banks.

The argument is delicate and deserves a flash-back to the origins of the euro. The birth of the single currency had spread among market participants the belief in the safe status of all central government debt [ARGHYROU, KONTONIKAS, 2010; ORPHANIDES, 2018]. Such a belief was the result of the equal treatment of all Eurozone governments’ debt securities within the ECB collateral policy and also of the prudential provisions for banks and asset management companies, that assign zero risk to sovereign exposures. But in the mid-2000’s the ECB has introduced a minimum credit-rating threshold to collateral eligibility, which – after the Deauville meeting – has led the monetary authority and the interbank market to apply different collateral haircuts to the bonds issued by different member States. This collateral discrimination and the deleveraging by banks resident in Central-Northern European countries have reinforced each other, contributing to the dissolution of the single yield curve of the monetary union and to the above mentioned nationalization of the public debts of Southern European countries.

Faced with the discrimination of bonds issued by their domestic governments, credit institutions within the periphery have been forced to ‘patriotically’ take over these sovereign exposures. Figure 18 offers a graphical evidence of this phenomenon, reporting the evolution of the share of public debt held by resident and non-resident investors for Italy, Portugal, Spain and Greece. The share held by non-resident investors has steadily increased up to 2007-2009, then it started declining for several years during the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis; eventually, since the beginning of the PSPP in March 2015, it has essentially stabilized on levels that, however, remain lower than those pre-crisis.

Figure 18 – Breakdown of public debt of peripheral countries held by resident and non-resident investors

The nationalization process took place in two main stages that essentially overlap with the most famous ECB’s extraordinary interventions of the last decade: the Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs) and the PSPP. Consistently, the nature of the resident investors (i.e., private banks and National Central Banks, respectively) that have played a leading role in each stage is strictly related to the specific features of the ECB intervention.

Figure 19 provides an aggregate picture of the public debt domestication in the periphery and shows graphically that it has been inversely correlated to the deleveraging by Franco-German banks.

Figure 19 – Public debt nationalization in the Eurozone periphery and deleveraging by French-German banks

With the two exceptional LTROs of December 2011 and February 2012, the ECB has injected 1 trillion euros in the banks of the monetary union in the form of central bank reserves. Most of this liquidity was taken up by peripheral credit institutions to cope with the sharp contraction of inter-bank funds. In particular, banks located in Italy and Spain had an aggregate uptake of approximately the 68% of the total aggregate uptake [DAETZ et al., 2016]. A large part of this central bank money was redirected to the purchase of domestic government securities that Franco-German banks were selling off; the remaining part was used to settle commercial liabilities owed to those same banks and to face the collapse of domestic deposits, which were departing for Northern Eurozone destinations [MINENNA, 2018a].

These dynamics have been particularly manifest for Italy: as shown in Figure 20, Italian lenders have taken up about 280 billion euros of LTROs and have used most of this amount to support the market value of the debt issued by their central government. A significant part of the remaining funds made available by the ECB served to repay commercial liabilities to banks located in Central-Northern European countries as these banks were scaling down also their exposures to Italian businesses and households.

Figure 20 – Public debt nationalization in Italy and ECB lending to Italian banks

In the case of Spain (see Figure 21), correlation between the variables at stake is less pronounced but still present. From March 2011 to September 2012 net ECB loans have soared by 300 billion euros, supporting the increase in the exposures of domestic banks to the government debt, even if the biggest slice has served to settle commercial liabilities with credit institutions located elsewhere in the Eurozone.

Figure 21 – Public debt nationalization in Spain and ECB lending to Spanish banks

Of course, it could be argued that by bearing the insolvency risk of peripheral banks on the enormous amounts disbursed with the LTROs, the European Central Bank has mutualized that risk across all member States. But, in this way, it has also allowed the segregation of risks inside the balance sheets of peripheral banks.

The targeted loans (T-LTROs) arrived between September 2014 and March 2017 have allowed peripheral lenders to turnover most of the LTROs liquidity and keep the degree of public debt nationalization at high levels.

The PSPP did the rest. There is no doubt that, by ensuring a stable and large demand for government bonds, the ECB has played a leading role in the narrowing of sovereign yield spreads, putting peripheral countries safe from the risk aversion of the markets. Nevertheless, at least two peculiar features of the PSPP architecture have been pivotal to the design of segregation of risks within the periphery: the capital key as criterion to allocate securities purchases across member countries and the negligible amount of risk sharing admitted on these purchases.

As known, the capital key represents the subscription share of each National Central Bank in the ECB capital and it has a direct correspondence with the contribute of each country to the population and economic growth of the European Community. The allotment of securities purchases in proportion to the capital key has favored countries (e.g. Germany and France) where deflationary pressures were much less relevant than in other countries (e.g. Italy and Spain) that, however, had a smaller capital key([20]).

The other specificity of the PSPP is the very limited risk sharing: only the 10% (initially only the 8%) of the purchases allotted to the debt of each member government is carried out directly by the ECB, whereas NCBs are appointed to buy the remaining 90% with funds borrowed from the ECB. As a consequence, each NCB results the only entity exposed to the default risk of its national government on purchased securities: in such an extreme scenario, it would bear the related losses while remaining obligated to repay to the ECB the full nominal amount borrowed. Precisely, what in finance is called Credit Default Swap (Minenna, 2015), where, indeed, NCBs act as protection sellers of the sovereign risk of their respective country to the rest of the Euro-system.

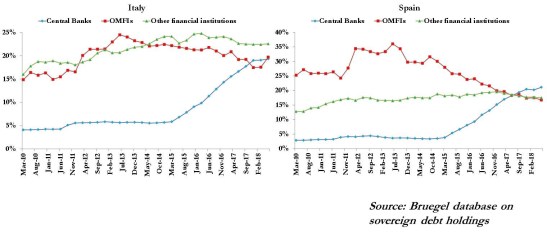

In this perspective, the main novelty of the PSPP with respect to the LTROs is that this time the nationalization of public debts takes place inside the balance sheets of National Central Banks rather than inside those of private banks.

Figure 22 highlights the trend just described for Italy and Spain, showing how from March 2015 (beginning of the PSPP) to June 2018 the sovereign debt held by the National Central Banks has climbed from around 5% to around the 20% of the total, accompanied by a downsizing (more marked for Spain) of the share of public debt held by the private financial system.

Figure 22 – Public debt nationalization in Italy and Spain: the role of National Central Banks during the PSPP

Apart from this novelty, risk segregation remains at work resulting in massive capital flights from Southern to Central-Northern European countries and in the abnormal phenomenon of negative yields, particularly pronounced for Germany because of its privileged position as recipient of bonds’ purchases by virtue of the capital key criterion.

Besides the nationalization of the peripheral public debts, the Euro-bureaucracy has also carried out a series of initiatives aimed at immunizing as much as possible foreign investors (especially those belonging to the Official Sector) against the sovereign risk of the peripheral States. These initiatives include not only the tightening of the European rules on public budget and debt sustainability (through the Six Pack and the Fiscal Compact) but also provisions aimed at facilitating the restructuring/reprofiling of the public debt of the countries with excessive debt.

In particular, the ESM establishing treaty has stipulated that, starting in January 2013, a growing share of new issues of Eurozone government bonds with maturity beyond the year would have embedded Collective Action Clauses (CACs) to make it easier to unlock resolution or restructuring solutions that are welcome by the Official Sector. In addition, CACs allow a qualified minority of bondholders to hinder the potential attempt of the issuing State to redenominate in a new currency government bonds that include such clauses [MINENNA, 2018b and 2018c].

In more recent times, as part of the debate on the reform of economic and monetary union, various proposals([21]) have been presented aimed at harnessing within national borders possible episodes of public debt crisis, for example by strengthening the institutional and legal underpinnings of sovereign debt restructuring [BUNDESBANK, 2016; ANDRITZKY et al., 2016; SCHÄUBLE, 2017; SAPIR, SCHOENMAKER, 2017; BÉNASSY-QUÉRÉ et al., 2018]. Some of these proposals have suggested the adoption of automatic restructuring mechanisms. This way, the restructuring solutions liked by the European establishment – typically those inspired by the ‘extend-&-pretend’ logic applied, for example, to the third Greek debt bailout – would automatically activate in front of predetermined trigger events without the need to achieve the green light from qualified majorities of bondholders([22]). The solution selected at the Euro-group of December 2018 – and endorsed in the same month by the European Council – provides for the switch of the CACs voting procedure from the current two-limb procedure to the single-limb procedure starting from 2022([23]). With the new voting procedure, the consensus expressed by a qualified majority of the holders of all affected bonds would be enough to give the green light to a restructuring proposal without the need to reach also a qualified majority of the holders of each bond series involved in the restructuring project (as instead currently foreseen)([24]).

The best indicator of the high degree of risk segregation in the euro area are the net Target2 balances of the different National Central Banks participating in the Euro-system. Target2 is the real-time cross-border interbank payment system for the Euro-system. Before the crisis, Target2 balances were essentially nil because the easy availability of interbank funding to banks to replenish shortfalls of their reserve accounts allowed an offsetting between current account and capital account [CECCHETTI et al., 2012]. But the crisis and the collateral discrimination policies made increasingly difficult for banks in peripheral countries to access interbank funds. As a consequence, interbank payment transactions between banks residents in different Eurozone countries began to involve their respective National Central Banks, which, in turn, began to experience increasing imbalances in their Target2 official settlements balance with the ECB. More precisely, as shown by Figure 23, National Central Banks of peripheral countries experienced growing Target2 deficits whereas those of core countries growing Target2 surpluses [DE GRAUWE et al., 2017; CESARATTO, 2017].

Figure 23 – Evolution of the net Target2 balances of Eurozone core and peripheral countries

In detail, it is possible to identify two distinct phases of enlargement of the Target2 imbalances [MINENNA, 2017a and 2017b]: the first one took place between 2009 and 2012-2013, while the second one has started in 2015. These timings are not random and, in fact, should be read and interpreted along with the main ECB interventions in the last ten years. In particular, the first diverging pattern overlaps with the above mentioned exceptional ECB lending activity (LTROs); in that period, the liquidity injected into the system by the ECB has de facto replaced the interbank funding for banks of the Eurozone periphery. The subsequent phase of re-absorption of the Target2 imbalances starts in has started with the announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions (second half of 2012) and with the begin of LTROs’ repayments. As for the second divergent pattern, it is chronologically superimposed on the launch of a new targeted loan program for European banks (T-LTROs) and of the QE, whose largest chunk is represented by the PSPP with the direct involvement of the National Central Banks in the bond-buying activity as above said.

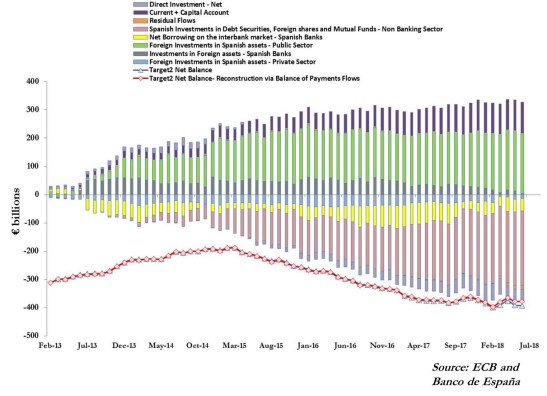

A compared analysis with the main components of the balance of payments offers interesting insights about the drivers of the Target2 imbalances [DOSI, MINENNA, ROVENTINI, 2018]. The larger and larger deficits displayed by Southern European countries between 2009 and 2012-13 essentially reflect the flight of foreign investors from the peripheral risk, the related nationalization of the public debts of peripheral governments and the collapse of the interbank funding opportunities for banks all around the Eurozone periphery.

With regard to the second sharp deterioration of the Target2 balances of peripheral NCBs, the comparison with the data of the balance of payments reveals a new phenomenon: the flight of domestic capitals towards safe havens located in Central and Northern Europe. As of March 2015 (beginning of the PSPP), non-financial private investors resident in countries such as Italy or Spain have moved their financial wealth from domestic assets – such as domestic government bonds – to foreign bonds, mutual funds and shares. Another salient feature of the second divergent pattern is the close correlation with the trend in the share of government bonds held by the National Central Banks. This confirms what was said above about the fact that the limited amount of risk sharing admitted by the PSPP has favored the nationalization of public debts while the pass-through effect of the monetary policy to the real economy has been rather limited since the liquidity deriving from the sale of government bonds to the NCBs has fled abroad [MINENNA, 2017a and 2017b; DOR, 2016; DOSI, MINENNA, ROVENTINI, 2018].

Figure 24 and Figure 25 give a graphical representation of the above described relationship between Target2 balances and the components of the balance of payments for Italy and Spain, respectively.

Figure 24 – Italy: Target2 Net Balance – Decomposition via balance of payments flows

The other coin side of the large negative imbalances of peripheral NCBs is the huge Target2 surplus recorded by the Bundesbank and other NCBs of core countries, such as Luxembourg, Finland and the Netherlands.

Target2 imbalances are among the strongest proofs of the systematic risk segregation that has characterized the European monetary union in the last decade and are at stake with the other anomalies discussed in this paper, such as the nationalization of peripheral public debts and the exceptional performance of the German current account.

Figure 25 – Spain: Target2 Net Balance – Decomposition via balance of payments flows

As long as the integrity and compactness of the euro area will be preserved, Target2 imbalances will remain accounting entries among the NCBs joining the Euro-system([25]). However, the situation would change if the Eurozone would break-up or a State would leave the monetary union. In an exit scenario, a ‘debtor’ National Central Bank might consider not to settle its Target2 liabilities with the rest of the Euro-system. This explains why Target2 imbalances have become one of the hottest issues of the scientific and institutional debate within the Eurozone.

The position expressed by the ECB President([26]) is that if a country were to leave the Eurosystem, its National Central Bank’s claims on or liabilities to the ECB would need to be settled in full.

In practice, however, no one can know in advance what would really happen in a similar scenario. Indeed, the central bank of a secessionist country with a high Target2 deficit could refuse to settle all or part of its ‘debt’ with the Euro-system, thus imposing a loss on the central banks of countries with a positive balance.

Several political and economic representatives from core countries have a completely different view: they claim that – since the advent of the crisis – Target2 has become an hidden bailout system for the periphery at the expense of the center of the Eurozone [HOMBURG, 2011; SINN, 2011; BAGUS, 2012]. They interpret the Target2 surplus of their NCBs as a credit to the periphery and have developed numerous proposals aimed at minimizing the risk of loss on these credits; for instance by freezing the current negative balances and introducing a new Target3 system subject to periodic settlement and backed by high-quality collateral [SINN, 2018; FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG, 2018]. More recently [MINENNA, 2019b]([27]), two political parties (FDP and AFD) have submitted to the German Parliament specific motions to guarantee the Bundesbank’s huge Target2 credit in the event of a debtor country leaving the euro area. In particular, FDP proposed that in such a scenario any Target2 liabilities of the leaving country should be previously converted into euro-denominated government bonds so as to hedge the Bundesbank against any possible loss, including that associated with the redenomination risk.

Yet, these proposals seem not to consider the actual causes of the huge Target2 imbalances, and of the divergent paths between the center and the periphery of the monetary union. In fact, the dynamics recorded by the Target2 system reflect large trade and financials imbalances that have progressively consolidated in the Eurozone and the big distrust of private investors in peripheral assets([28]).

These imbalances make membership in the Eurozone less and less sustainable for peripheral countries and represent a constant concern for core countries and for financial markets. No coincidence that some experts have discussed about the need for an exit clause from the Eurozone([29]).

Similarly, trends in real sovereign spreads – already examined in Section 2 – reflect the risk imbalance between the center and the periphery of the euro area. This is not surprising given that real spreads are clearly linked to Target2 balances. For example, if a German bank disposes of a BTP by selling it to an Italian bank, the settlement of this transaction will result in an increase in the Target2 balance of the Bundesbank and a simultaneous reduction in that of the Bank of Italy; at the same time, the sale of the BTP will create upward pressure on the Italian spread. Also cross-country trade deals entail financial flows that are relevant for both spreads and Target2. If, for example, an Italian family buys a car from a German company, the Target2 balance of the Bank of Italy will worsen, that of the Bundesbank will improve; meanwhile the greater demand for cars will contribute to reinvigorate inflation in Germany and to increase the spread in real terms.

The link between real spreads and Target2 balances is particularly evident for Italy and can be grasped, as a first approximation, by a simple graphic comparison between the dynamics of the two quantities (Figure 26). Since the beginning of the crisis, Italy’s real spreads and Target2 balances have moved in unison, albeit in opposite directions: while the spread went up, the Target2 balance fell.

Figure 26 – Italy: Target2 Net Balance and real sovereign yield spread

In order to quantify the relationship between Target2 imbalances on the one hand and real sovereign spreads on the other, it is useful to explore how much of the spread variability is explained by Target2 dynamics through ordinary least squares (OLS) techniques, after controlling for other variables that may have significantly affected real spread dynamics.

Over the period from January 2010 to August 2019, the most significant event in terms of downward pressure on interest rates in the Eurozone and, therefore, also on the level of spreads, was undoubtedly the PSPP carried out by the ECB from March 2015 to December 2018. I thus estimated a linear OLS model by regressing the real 10-year BTP-Bund spread on the Target2 balance (in billions of euros) of the Bank of Italy and on a dummy variable which is equal to 1 in the period from March 2015 to December 2018 and zero otherwise (the model also encloses an intercept).

The following table displays the regression output.

| Linear Regression Model: y ~ 1 + x1 + x2

|

||||

| Estimated Coefficients: | ||||

| Estimate | SE | tStat | pValue | |

| (Intercept) | 159.8 | 8.8139 | 18.13 | 3.0629e-35 |

| x1 Target2 balance (€ billions) |

-0.48446 | 0.035893 | -13.497 | 2.6099e-25 |

| x2 Dummy PSPP | -104.42 | 11.818 | -8.8361 | 1.4933e-14 |

| Number of observations: 116, Error degrees of freedom: 113

Root Mean Squared Error: 52.1 R-squared: 0.621, Adjusted R-Squared: 0.614 F-statistic vs. constant model: 92.6, p-value = 1.54e-24 |

||||

The R2 of the regression is 62.1% and all estimated coefficients are statistically significant, confirming the strong (inverse) connection between Target2 and real spread movements. More in detail, on average (and after controlling for the PSPP), an increase of 100 billion euros in the Target2 liabilities of the Bank of Italy results approximately in an increase in the real spread of around 48 basis points.

Figure 27 compares the observed real spread with its fitted values according to the estimated coefficients of the linear model.

Figure 27 – Italy: Observed versus Fitted Real sovereign yield

The inverse relationship between real sovereign spread and Target2 balance has been experienced also by Spain, as shown in Figure 28, but for a shorter time period. In fact, it has progressively faded since years 2014-2015, roughly at the time when it became clear that the ECB would have started a large-scale asset purchase program and that the Spanish leading political class would have accommodated the requests of the Euro-bureaucracy.

Something similar can be argued also with regard to Italy if focusing on the very end of the observation period: the circumstances are pretty the same as those just mentioned for Spain, that is the evident approaching of a new season of monetary stimulus and the fading of the Euro-adverse attitude in Italian government parties.

Figure 28 – Spain: Target2 Net Balance and real sovereign yield spread

4. Large competitiveness gaps and prolonged risk segregation raise serious concerns about the compactness and resilience of the Eurozone. The symptoms of this controversial set-up are manifold: social discontent, prolonged absence of fiscal stimuli despite an anemic growth, exacerbation of the Euro-skeptical debate, rise of political parties featuring a confrontational attitude toward the European institutions.

So far the broad compliance of national governments with the rules and the guidance defined by the Euro-bureaucracy and the implementation of austerity-based domestic reforms have allowed – in the context of an accommodative monetary policy – the Eurozone to stay alive.

However, since the beginning of the crisis, the economic and monetary union physiognomy has changed profoundly.

Because of the systematic segregation of risks, the dichotomy between center and periphery – which in the early years of the euro had remained under track – has exacerbated, becoming an important component of the sovereign risk of the peripheral countries.

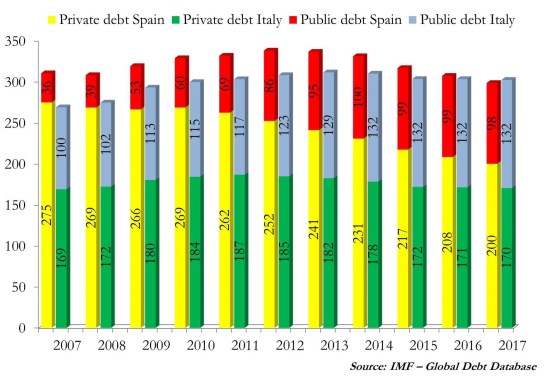

This explains why, in the post-Deauville era, the risk indicators of Italy and Spain – the two largest peripheral economies – have shown very similar trends despite their differences, for example with regard to the different balance between public and private debt. In Spain the private component represented the 75% of the total debt and the public debt represented only the remaining 25%, while in Italy the situation was more balanced, with government bonds around 40% of the total debt of the country and projected in a trend of increasing incidence as it happened in fact (see Figure 29).

Figure 29 – Spain and Italy: private and public debt in GDP terms

It should however be noted that the two countries were very similar in terms of aggregate leverage (both around the 300% of GDP), which – along the common belonging to the Eurozone periphery – explains why the markets’ assessment of their risk profile was similar.

In practice, given the then current European regulation on risks markets’ participants were expecting that a private debt crisis would have been addressed through subsidiarity by the public sector and vice versa.

And actually so it was. The crisis in the Spanish banking sector in 2012 was managed through the establishment of a bad bank owned by the government – and backed by the ESM also to avoid losses to the Franco-German banks heavily exposed to Spanish counterparties([30]) – which over the years have translated in an increase of about 25 percentage points in the public debt-to-GDP ratio. On the other hand, in Italy the banking system – supported by the ECB’s LTROs – has bought government bonds for over 200 billion euros in order to absorb the excess supply of these securities due to the deleveraging of foreign banks, many of which resident in core Eurozone countries.

It is no coincidence therefore that the two spreads (ie, BTP-Bund and BONOS-Bund, respectively) have shown quite aligned trends for several years hence qualifying a proxy of the peripheral risk within the Eurozone.

However, starting from the last quarter of 2016, the transition to a new structure began in which Italy has progressively deviated from the other peripheral countries and its risk profile has worsened for reasons that go beyond the high public debt-to-GDP ratio (which, in a certain way, represents a structural feature of Italy and is offset by one of the highest private savings in the world).

Figure 30 confirms the pattern just described by contrasting the two spreads.

Figure 30 – Nominal yield spread of Italian and Spanish 10-year government bonds with respect to the German Bund

The progressive isolation of Italy within the Eurozone appears due to a gradual deterioration of the interaction with the European interlocutors([31]), developed partly in response to a series of regulatory decisions and supervision of the European institutions that have put the spotlight on Italy.

Indeed, the European Union has tightened budgetary discipline and surveillance – with particular attention to issue of public debt sustainability and, thus, also of the excessive values of the debt-to-GDP ratio – while it has clearly adopted a softer approach towards other macroeconomic imbalances, such as those deriving from the excessive private debt or trade surplus.

Furthermore, Europe has adopted increasingly stringent regulations on the banking system. Provisions on burden sharing (August 2013) and, later, on bail in (January 2016) have reduced the possibility of intervention by national governments to support their banks in crisis. For Italy, this new regulatory framework intervened after the banking system had made a huge effort in terms of public debt nationalization. Until that time, Italian banks had not benefited from significant State support measures as had happened in many other member countries, even in the form of large cash disbursements.

The tightening of the rules on credit institutions also concerned the increasingly severe treatment of non-performing loans – in terms of precautionary provisions and of pressures for a rapid disposal of these exposures – to be considered almost a regulatory obsession if compared to the substantial indifference of Europe to the risks of structured finance exposures very common in the balance sheets of the banks of the main member countries with the exception of Italy. The new regulation has exacerbated the negative and pro-cyclical effects of the banks-sovereign doom-loop and increased the power of the spotlight on Italy, fueling the perception that the country had now become the sick man of Europe.

The described strengthening of the European provisions and oversight on national public accounts and banking systems has contributed to nourish a growing intolerance of a part of the Italian public opinion towards the European institutions also because of some unpopular measures adopted by governments over time in order to comply with European constraints, such as the pension reform at the end of 2011 and the management of some serious banking crises with high losses for the citizens-savers.

Starting from the last months of 2016, this discontent was compounded by a climate of growing political uncertainty linked to the constitutional referendum and related change of government but also, during the first months of 2017, to the developments of the presidential campaign in neighboring France (where it seemed possible the victory of anti-Europeanist parties). All this has contributed to increasing the risk perception by the financial markets.

After a pause in the second half of 2017, Italy has started again to move away from Spain with the overheating of the campaign for the March 2018 political elections; the divergence process then accelerated starting in May of the same year in conjunction with the formation and establishment in Italy of a critical government towards Europe.